Begrudgingly, Japan is beginning to accept that it needs more immigrants

IN THE Shin-Okubo neighbourhood of Tokyo, smells of Korean food and snatches of the language waft in the air. A supermarket selling kimchi sits next to an Indian-run kebab shop—the latter complete with leaflets promoting Islam, the religion of the Calcutta-born owner. A local estate agent advertises staff that speak Chinese, Vietnamese and Thai alongside the floor plans for tiny Tokyo apartments.

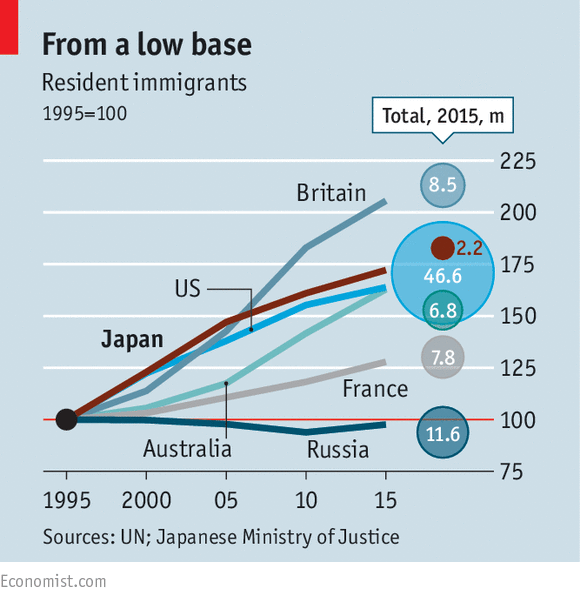

Shin-Okubo is a rarity in Japan. The country has remained relatively closed to foreigners, who make up only 2% of the population of 127m, compared with an average of 12% in the OECD, a club of mostly rich countries. Yet Japan is especially short of workers. Fully 83% of firms have trouble hiring, according to Manpower, a recruiting firm, the highest of any country it surveys. And the squeeze is likely to become much worse. The population is projected to drop to 87m by 2060, and the working-age population (15-64) from 78m to 44m, because of ageing. The Keidanren, the Japan Business Federation, and prominent business leaders such as Takeshi Niinami, the head of Suntory, a drinks company, have long called for more immigration.

Shinzo Abe, Japan’s prime minister, says he would prefer to raise the relatively low proportion of Japanese women who work, and to keep all Japanese working later in life, before admitting droves of foreigners. But his government has nonetheless taken a few small steps to boost immigration. It has quietly eased Japan’s near-ban on visas for low-skilled workers, with agreements to allow foreign maids to work in special economic zones. It is now talking about relaxing requirements for Filipino carers. The authorities have also made student and trainee visas easier to obtain, and turned a blind eye to those who exploit them to recruit staff for jobs that involve very little study or training at kombinis (the ubiquitous corner stores, often staffed by Chinese) or in forestry, fishing, farming and food-processing. It may extend trainee visas from three years to five. Mr Abe has also boasted that he will reduce the time non-permanent residents need to live in Japan before becoming eligible for permanent residence to the “shortest in the world”—probably to less than three years (far from the shortest) from the current five.

All this is starting to make a difference. Last year the number of foreign permanent residents reached a record 2.23m, a 72% increase on two decades ago—and the number of people on non-permanent visas is also rising. But the goal seems to be a surreptitious increase in the number of temporary workers and a more accommodating system for skilled workers, not the settlement of foreigners on a grand scale. Only tiny numbers of foreigners become Japanese citizens (see article) and even fewer are granted asylum: only 27 in 2015, a mere 0.4% of applicants.

A few voices advocate opening the door more widely. Hidenori Sakanaka, a former immigration chief who now heads the Japan Immigration Policy Institute, a think-tank, reckons Japan needs 10m migrants in the next 50 years. At the very least the country needs a clear policy on bringing in menial foreign workers, rather than ignoring the abuse of student and trainee visas, says Shigeru Ishiba, a prominent lawmaker in the Liberal Democratic Party who is expected to challenge Mr Abe for the party’s leadership in 2018. The government needs to lay out the specifics of how many people it wants to attract and in what time-frame, he says.

Public opinion seems to be gradually shifting. The authors of a recent poll by WinGallup were surprised that more Japanese favoured immigration than were against it—22% to 15%—although a whopping 63% said they were not sure. A warm embrace for lots of foreigners is unlikely. Japan’s nationalists do not have the power of Europe’s broad-based anti-immigrant movements. But the country prides itself on its homogeneity, and although the media no longer reflexively blame foreigners for all social ills, discrimination is still rife. Many landlords will not accept foreign tenants, ostensibly, says Li Hong Kun, a Chinese estate agent in Shin-Okubo, because they do not adhere to rules such as being quiet after 10pm and sorting the rubbish properly (a complex task). Others suggest terrorist attacks in Europe as a reason to keep Japan for the Japanese. Brazilians of Japanese origin, who were encouraged to migrate to Japan in the 1980s, have never really been accepted despite their Japanese ethnicity, notes Tatsuya Mizuno, the author of a book on the community.

Even Mr Sakanaka and Mr Ishiba think all migrants must learn the language and local customs, such as showing respect for the imperial family. But the economic case for a bigger influx is undeniable. For those, like Mr Abe, who speak of national revival, there are few alternatives.