Britain’s oldest nuclear plant closed on Wednesday, leaving in its wake a £700m decommissioning bill and further questions about the UK’s ability to keep the lights on.

The closure of the Wylfa plant in Wales after 44 years of service puts more pressure on EDF Energy to take a final investment decision for new reactors at Hinkley in Somerset.

The station on the island of Anglesey generated enough electricity to power 1m homes, and with a capacity of 1,000MW was once the largest facility of its kind in the world. But after an earlier life extension scheme expired, the last of the 26 British-designed Magnox reactors was switched off by the private consortium that manages the plant for the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (NDA).

The site was due to close in 2010 but it was kept open for a further five years as fears mounted that Britain would face an electricity shortage because new atomic and gas-fired power plants were not being constructed. “Wylfa has been a terrific success story for Anglesey and the UK nuclear industry. We have generated safely and securely for many years, which is an excellent achievement,” said Stuart Law, the site director.

It will take another 10 years for the basic decommissioning to be undertaken at a cost of about £700m but the site cannot be redeveloped before the end of the century. High-level waste from Wylfa will remain on Anglesey until a national nuclear waste disposal facility is finally developed.

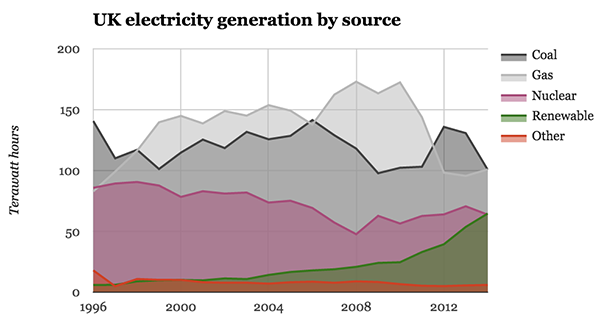

Britain still has a fleet of advanced cooled atomic reactors run by EDF but most of these will be retired by 2023 just as the government has also promised to halt all coal-fired power stations.

Hitachi of Japan is leading a Horizon Nuclear Power project to construct a new power plant at Wylfa, with a second earmarked for Oldbury in south Gloucestershire alongside a third facility planned in Cumbria. But the atomic industry’s revived fortunes ride primarily on the Hinkley C plant, which is expected to be the first new site since the Sizewell B station was completed in 1995.

The £18bn Somerset project has been repeatedly delayed but Chinese investors finally gave their support in the autumn while the government promised the latest in a series of subsidies. EDF signalled in October that it would start work at Hinkley and it is expected to give the formal investment the go ahead within weeks before later saying it may not come until after Christmas.

Hinkley Point C, intended to provide about 7% of the UK’s total electricity, was originally scheduled for completion by 2018 but the latest date is 2025. Sceptics still question whether it will make that later date given the experiences of delays and cost overruns with a similar power project at Flamanville in Normandy, northern France.

There have also been problems at the new Olkiluoto nuclear plant in Finland which is using the same plant design provided by EDF’s engineering partner Areva at Flamanville and planned for Hinkley.

National Grid, Britain’s electricity network operator, has played down the significance of the Wylfa closure and says it has put special measures in place to meet any mid-winter peaks in power demand. Another milestone in the change of Britain from a high to a lower carbon energy producer came two weeks ago when the country’s last deep coal mine, at Kellingley in North Yorkshire, closed.

SOURCE: http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/dec/30/wylfa-nuclear-plant-closes-in-wales

The closure of the Wylfa plant in Wales after 44 years of service puts more pressure on EDF Energy to take a final investment decision for new reactors at Hinkley in Somerset.

The station on the island of Anglesey generated enough electricity to power 1m homes, and with a capacity of 1,000MW was once the largest facility of its kind in the world. But after an earlier life extension scheme expired, the last of the 26 British-designed Magnox reactors was switched off by the private consortium that manages the plant for the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (NDA).

The site was due to close in 2010 but it was kept open for a further five years as fears mounted that Britain would face an electricity shortage because new atomic and gas-fired power plants were not being constructed. “Wylfa has been a terrific success story for Anglesey and the UK nuclear industry. We have generated safely and securely for many years, which is an excellent achievement,” said Stuart Law, the site director.

It will take another 10 years for the basic decommissioning to be undertaken at a cost of about £700m but the site cannot be redeveloped before the end of the century. High-level waste from Wylfa will remain on Anglesey until a national nuclear waste disposal facility is finally developed.

Britain still has a fleet of advanced cooled atomic reactors run by EDF but most of these will be retired by 2023 just as the government has also promised to halt all coal-fired power stations.

Hitachi of Japan is leading a Horizon Nuclear Power project to construct a new power plant at Wylfa, with a second earmarked for Oldbury in south Gloucestershire alongside a third facility planned in Cumbria. But the atomic industry’s revived fortunes ride primarily on the Hinkley C plant, which is expected to be the first new site since the Sizewell B station was completed in 1995.

The £18bn Somerset project has been repeatedly delayed but Chinese investors finally gave their support in the autumn while the government promised the latest in a series of subsidies. EDF signalled in October that it would start work at Hinkley and it is expected to give the formal investment the go ahead within weeks before later saying it may not come until after Christmas.

Hinkley Point C, intended to provide about 7% of the UK’s total electricity, was originally scheduled for completion by 2018 but the latest date is 2025. Sceptics still question whether it will make that later date given the experiences of delays and cost overruns with a similar power project at Flamanville in Normandy, northern France.

There have also been problems at the new Olkiluoto nuclear plant in Finland which is using the same plant design provided by EDF’s engineering partner Areva at Flamanville and planned for Hinkley.

National Grid, Britain’s electricity network operator, has played down the significance of the Wylfa closure and says it has put special measures in place to meet any mid-winter peaks in power demand. Another milestone in the change of Britain from a high to a lower carbon energy producer came two weeks ago when the country’s last deep coal mine, at Kellingley in North Yorkshire, closed.

SOURCE: http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/dec/30/wylfa-nuclear-plant-closes-in-wales